Farrokh

Active Member

VFX Supervisor Paul Franklin Talks Batman Begins

Comic pro Danny Fingeroth talks with Double Negative’s visual effects supervisor Paul Franklin about bringing Batman Begins to the big screen.

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]

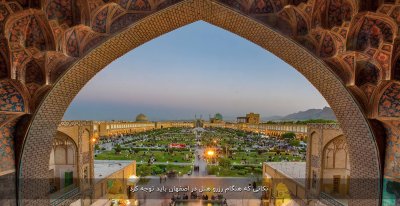

Visual effects supervisor, Paul Franklin, enters Gotham City. All images courtesy of Double Negative. © 2005 Warner Bros. Ent. All rights reserved.

Visual effects supervisor, Paul Franklin, enters Gotham City. All images courtesy of Double Negative. © 2005 Warner Bros. Ent. All rights reserved.

For its most ambitious project to date, London-based Double Negative created more than 300 vfx shots for Batman Begins, led by in-house visual effects supervisor Paul Franklin. This necessitated revamping its design facility, creating a new working pipeline and installing new infrastructure to handle the workload. Franklin tells comic expert Danny Fingeroth how Double Negative helped to seamlessly create Gotham City and its role in digitally assisting with many of the other Bat happenings. [/FONT][FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]Danny Fingeroth: How did the visual effects you worked on help to make Batman, a superhero who’s not actually superhuman, seem bigger than life? [/FONT]

For its most ambitious project to date, London-based Double Negative created more than 300 vfx shots for Batman Begins, led by in-house visual effects supervisor Paul Franklin. This necessitated revamping its design facility, creating a new working pipeline and installing new infrastructure to handle the workload. Franklin tells comic expert Danny Fingeroth how Double Negative helped to seamlessly create Gotham City and its role in digitally assisting with many of the other Bat happenings. [/FONT][FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]Danny Fingeroth: How did the visual effects you worked on help to make Batman, a superhero who’s not actually superhuman, seem bigger than life? [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]Paul Franklin: The key thing for this movie, throughout production and post-production, and in every aspect, is that [director] Chris Nolan really wanted this to be very much grounded in some sort of believable reality, rather than existing purely inside some sort of graphic world that could only be achieved through the use of computer animation or whatever. And he always wanted to make it feel like that you might actually go to Gotham, that Gotham might be a real place and that somebody could really do the things that Batman was doing. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]So, particularly with our work for creating the character of Batman, the majority of what you’re looking at on film is real stuntwork. It’s either Christian Bale dressed as Batman, or his stunt double, Buster, who did some incredible stuff. And there was some amazing work put together by the stunt crew for the show. But there were a few moments where we used digital effects to basically extend what the stunt crew had already achieved, and just basically carry the action off in ways that perhaps are a little bit too hard to rig at the moment. For instance, Batman is equipped with various types of high technology that he uses in his battle against crime. He has the ability to fly — or, to be more precise — to glide, with the aid of the Bat-cape. And the special effects guys put together a really impressive flying rig for Batman. But one thing that it wasn’t really capable of doing was deploying in flight. So, for instance, when Batman jumps off the top of a building and goes down the side of a building, and then his loose-flying cape suddenly deploys into the hang glider shape, bat-wing shape — that’s something we achieved digitally, through digital stunt double work. But, at every point, Chris Nolan was really, really keen that it shouldn’t look like this guy has suddenly sprouted wings and is able to fly like a bird-man. He basically is now turned into, say, a hang glider or a parasail, or something like that. And so that effect was based on: what might it be like if this guy was equipped with some kind of high-tech parafoil? How might he fly? [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]DF: Well, you certainly achieved that. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: Batman’s not capable of incredible muscular feats that would require him to be superhuman and have unbelievable, godlike strength. But he’s equipped with this incredible Kevlar body suit that has an endoskeleton, and all this sort of stuff. So that’s the type of thing we were doing. And in order to make that all work, we had to, first off, make very, very detailed models of Christian Bale dressed as Batman in the Batman costume. We had to study the Batman costume so we could reproduce it with fidelity in the digital world, so that you wouldn’t notice the difference between the digital Batman and the live-action Batman. Because we actually cut seamlessly within a couple of shots from a stunt double to the fully digital Batman. We wanted to make sure that was seamless, because we didn’t want it to certainly look like it was turned into an animated character at that point. And then, when we we’re doing the stuff that we’re doing as digital effects, we’re always basing it on some sort of actual reference. So, for example, for the shot in the movie, where you see Batman dive down the side of a building and then deploy his wings and “fly,” it’s an entirely digital shot. We actually had access to Buster, and he and the stunt crew staged the special reference stuff for us. Buster went up on top of one of the large buildings inside the giant set in Cardington, which is about eight stories high, and did a wire jump off the side of the building — which he repeated 10 times. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]We mounted 10 video cameras manned by members of the Double Negative visual effects team, and recorded Buster from every possible angle doing this repeated action. He did it with and without the bat wings, so we could get a feel for how he might fall, and how the wings might behave in the slipstream. So all our stuff was always based on some sort of actual reference that we always have.[/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif] DF: Is there anything you want to add about the effects being seamless and fitting in with the overall naturalistic look of the film? [/FONT][FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: Chris is a very interesting filmmaker in that he’s a young guy and he has a very hands-on approach to filmmaking. Now, Batman Begins is a very big-budget film, probably one of the biggest-budget films made this year. Quite often, in that kind of filmmaking, the director will spend a lot of time working with the principal cast and crew, but he’ll let stunt sequences and visual effects sequences be handled by a second unit. Well, with this film, there was no second unit. Chris and Wally Pfister, the director of photography, shot everything. Every frame you’re looking at there has pretty much been authored by Chris and Wally. They’re involved. Chris is involved in everything that went into the film. And what’s also very interesting about this film is that they’re very into the whole technology of filmmaking in the traditional sense, in that this film does not have a digital intermediate. It wasn’t taken to a digital lab. It’s all graded in the traditional way, in a film laboratory. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]

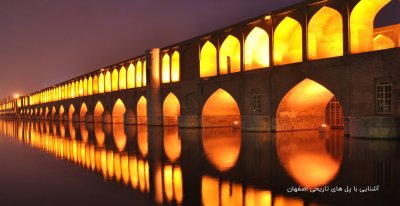

Chris Nolan’s control of the look of the film even extended to grading the film in a film lab instead of using a digital intermediate.

Chris Nolan’s control of the look of the film even extended to grading the film in a film lab instead of using a digital intermediate.

DF: How so? [/FONT][FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: It was very important to Chris and Wally that all our digital work fit in seamlessly with that, so we had to prove at a very early stage that we were going to be able to faithfully mimic the actual photochemical filming process with our digital tools. And this set the standard for the way that we then have to work on the movie, because to prove something to Chris Nolan, who’s not somebody who’s done a huge number of digital effects in his previous films — what he would like to do is go out, film something for real and then go away and make a digital version of the same thing and put them side by side. And when he agreed that they both looked the same, that’s when we passed the test, that’s when he’s happy that the work’s going to go into the film. [/FONT]

DF: How so? [/FONT][FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: It was very important to Chris and Wally that all our digital work fit in seamlessly with that, so we had to prove at a very early stage that we were going to be able to faithfully mimic the actual photochemical filming process with our digital tools. And this set the standard for the way that we then have to work on the movie, because to prove something to Chris Nolan, who’s not somebody who’s done a huge number of digital effects in his previous films — what he would like to do is go out, film something for real and then go away and make a digital version of the same thing and put them side by side. And when he agreed that they both looked the same, that’s when we passed the test, that’s when he’s happy that the work’s going to go into the film. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]It was this level of scrutiny that was applied to every aspect, whether it was creating the digital reproduction of the way that a camera actually captures the light, to the way that we had to prove that we could do convincing, photorealistic digital architecture to be able to create the digital cityscapes of Gotham City. We actually went out and we chose a suitably art deco building here in London and photographed it on a variety of different films and still formats, on an extremely cold day here in January about a year ago. We filmed the sun rising, so we were there before the dawn. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]That was also an interesting foresight of what was to come, because we were perched on the tops of buildings, looking at this other building, in fairly precarious positions. And eventually we ended up in Chicago, standing on top of the very top ledge of the Sears Tower photographing the dawn rising over Lake Michigan. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]DF: Tell us more about the lighting and modeling used to achieve the effects that you wanted. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: Well, Chris isn’t somebody who will come up with a whole bunch of storyboards and approve a whole bunch of previsualization animation, and say, “OK, this is what we’re going to do for the film.” He was very keen that this film should not be overwhelmed by CGI and end up becoming a cartoon. This extended all the way back to the pre-production process, where he didn’t want to produce animatics. He didn’t want to have, say, a story reel of the film, which he would then just go out and shoot. He likes to make a lot of his creative decisions when he’s actually on the set, because it might be that the actors respond differently to actually being in Chicago or something like that, and get some interesting things that you couldn’t predict were going to happen. If you’ve got this sort of predefined, rigid structure, which you’re going to shoot, then you can’t respond to that, you can’t make use of it. So he would often see things and say, “OK, this is a cool thing, this is what I want to get in the film.” However, we had to be able to plan for what we were going to do to be able to create the digital environments later on. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]And so we went out in May for a two-week visual effects shoot, which is in advance of the main unit turning up in August in Chicago. We knew there were a variety of locations that were going to be in the film, and a variety of different types of environments that we needed to get, but we didn’t know exactly what they would be, and where the camera was going to be pointing and how the scene was going to be lit. So we developed a process that allowed us to photograph very high-resolution panoramas of the Chicago cityscape across a very wide range of exposure. This means that we could take environments that we’d shot under ambient Chicago city light conditions — in other words, just the lighting you would see if you went to Chicago this evening and pointed a camera at the buildings — and then, because we had this very, very high dynamic exposure range, we could then relight these images through the use of computer graphics so we could match the theatrical lighting, which Wally then put on the locations when the main unit showed up later in the year. They used some pretty impressive lighting rigs on the days when they were shooting stuff, particularly for the car chase sequence, when the Batmobile is on the rooftop of the parking garage just before it leaps off and goes into the crazy chase across the rooftops, which is all our work. We had to match all the environments around the miniature car chase sequence to match everything that came before that. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif] The other thing is that we had to build, for modeling, a very comprehensive library of Chicago structures, and also other structures that were hero buildings, like Wayne Tower, for example, which was an imaginary building which doesn’t really exist, obviously. Whenever you see Wayne Tower in the film, it’s an entirely digital creation. So that was something very key, to get it looking totally convincing and integrate it into the Chicago cityscape, to then create the landscape of Gotham.[/FONT] [FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]

One of the major architectural additions was the Wayne Tower.

One of the major architectural additions was the Wayne Tower.

DF: How big an adjustment was it for Nolan to work digitally? [/FONT][FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: Chris, I think, was kind of worried that we would obscure everything behind technicality. He was slightly suspicious that the digital visual effects guys might try and pull the wool over his eyes, and steer the film into a direction they wanted to take it in. So we had to make sure that all of our tools worked in a way that was understandable to people who are involved in the business of going out and shooting pictures and who talk in terms of traditional cinematography. [/FONT]

DF: How big an adjustment was it for Nolan to work digitally? [/FONT][FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: Chris, I think, was kind of worried that we would obscure everything behind technicality. He was slightly suspicious that the digital visual effects guys might try and pull the wool over his eyes, and steer the film into a direction they wanted to take it in. So we had to make sure that all of our tools worked in a way that was understandable to people who are involved in the business of going out and shooting pictures and who talk in terms of traditional cinematography. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]Now, basically, our 3D lighting toolset was designed to mimic the way you would work on a real set, instead of working in arbitrary values of intensity of light and things like that. You can do things in a 3D universe, which are completely non-naturalistic. They don’t obey any laws of physics. And this was the sort of thing that Chris objected to. He would say, “Well, as soon as you start breaking the rules, then the scene inherently loses its believable look. It starts looking like a cartoon. It starts looking like a contrivance.” So we were very keen to make sure that our office would always talk in terms of photographic stops. And so they would say, “OK, so you want to raise the exposure on this scene?” Rather than just, “Make it brighter, increase the intensity by this amount,” you actually talk in terms of photographic stops. And so if Chris would say to us, “OK, that needs to be two stops brighter,” I could say to my 3D artists, “Make it two stops brighter,” and it all meant the same thing to everybody. We all used the same language. That was quite conscious. So it was more about making the digital environment user-friendly. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]DF: It’s the way a computer interface becomes simplified. You don’t need to know all sorts of code to use it. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: Exactly. One of the key things is also that it means that our artists are also thinking in a more creative, more artistic fashion. They’re not looking at everything through the interface of all the technical layers that get laid on top, and they start thinking more about, “What is it I’m actually doing here? What am I actually doing with these images? How am I making these images so that they evoke an emotional response, that they fit with the feeling of the live-action photography, and that they tell a story?”[/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif] DF: What was gained by using a virtual city, albeit one based on real places, instead of simply going on location in an actual city? [/FONT][FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: One of the key places where Batman Begins really goes into the realms of the fantastic is that the sheer scale of Gotham City is way beyond anything that you could ever see in a real city. Now, Chicago is incredibly impressive. If you go up to the top of the Sears Tower and look out, you think, “This is quite an incredible landscape.” Especially compared to anything we have over here in Europe. I mean, London’s an enormous city, but it just doesn’t have that sheer gargantuan size at the center of it that big American East Coast cities have. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]At the same time, Chris really wanted it to feel like Gotham’s a city out of control, sprawling in all directions, a true mega-city. There’s a moment quite early on in the film, where Bruce is returning from his sojourn in the Himalayas, and he’s flying back into Gotham with Alfred on board the Wayne Enterprises private jet. Bruce looks out of the window and he sees the sun rising over Gotham City as they fly in from the sea, and the sun is glittering off the sea — that’s an entirely computer-generated shot. There’s no live action in that shot. Everything that you’re looking at there is computer-generated. But it’s always based on a reality. All of the buildings in the city are based on Chicago originals, and the look and feel of it is inspired by the way that New York is broken up into islands. The lighting design is based on the photography that I did from the top of the Sears Tower, watching the sunrise over Lake Michigan. But the scale of it is enormous. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]DF: So Wayne Tower is the only made-up building in the thing? [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: Yes, although, obviously we have things like the monorail system, which is a non-real thing. That was inspired by the Chicago El train, but it’s been taken into the realm of the fantastic by suspending it 150 feet up in the air with these incredible sort of mid-twentieth century ironwork structures. It has this almost sort of Victorian, industrial revolution feel to it. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]DF: Was that based on actual designs, actual buildings from the Victorian era? [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: What they were all based on was the actual structure of the Cardington, the building that was used here in the U.K. as a studio, which is a vast hangar, which was built just after the First World War to house an airship called the R-101, which was the size of the Hindenburg — 800 feet long. The building is quite incredible. It’s a single structure, one giant room, which is about 200 hundred feet high and about 200 feet wide, and a quarter of a mile long. But it’s supported by this unbelievable grid structure inside of it, the girder structure that supports the roof, and that was the inspiration, I believe, for the monorail towers.[/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]

One of the digital touches added to Chicago to transform it into Gotham City was the monorail system.

One of the digital touches added to Chicago to transform it into Gotham City was the monorail system.

DF: Are there any scenes you worked on that are obviously vfx? [/FONT][FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: With visual effects work, you have stuff that ranges from big, key moments — like, say, the end shot of the movie, or that big cityscape or any of these big establishing city shots of Gotham where we’ve extended the scenes, and that’s obviously stuff where people will probably notice that something was done. But then you go all the way down to the other end of the scale, where you’ve got straightforward things like wire removals, where you’re just taking out wiring and things like that and preparing the background, removing a bit of camera apparatus, which you didn’t want to see, that sort of thing. That’s obviously stuff that people might not notice that there’s any visual effects work. [/FONT]

DF: Are there any scenes you worked on that are obviously vfx? [/FONT][FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: With visual effects work, you have stuff that ranges from big, key moments — like, say, the end shot of the movie, or that big cityscape or any of these big establishing city shots of Gotham where we’ve extended the scenes, and that’s obviously stuff where people will probably notice that something was done. But then you go all the way down to the other end of the scale, where you’ve got straightforward things like wire removals, where you’re just taking out wiring and things like that and preparing the background, removing a bit of camera apparatus, which you didn’t want to see, that sort of thing. That’s obviously stuff that people might not notice that there’s any visual effects work. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]DF: But, say, the scene on the glacier — were there any visual effects done on that? [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: The big moment in the scenes in Iceland is when we establish the monastery for the first time, where you see the monastery on the side of a mountain through a snowstorm. And the monastery is a miniature, of course, because there isn’t a real monastery that looks like that, and there certainly isn’t one in Iceland. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]But everything that you’re looking at in terms of the environment in those scenes, with the snow falling, all that sort of stuff, that’s all been created digitally, as well. I’d say that’s an example of scene effects where people wouldn’t notice that something was going on. Perhaps the best moment for that is, at the end of that whole sequence where Bruce Wayne is walking towards the private jet parked out on the runway. That was actually shot at a rather rainy airfield north of London, so surrounding the plane was just flat, green, rolling fields, and some housing in the far distance. We replaced the background with a digital matte painting, which I think is pretty seamlessly integrated there. It makes it look like you’re still in the Iceland environment. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]DF: Were there any visual effects you tried for in the movie that didn’t work and couldn’t be used? [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: I’d say no. There wasn’t really anything that we tried that didn’t work out, because we were in a very lucky position on with this film. We got involved on the movie right at the beginning, during preproduction. We were involved in all of the pre-planning phase, so we were able to actually sit down with the guys and work out the best way of going about shooting things, and what kind of material we needed to get, and what kind of tools that we needed to develop. We then were able to have a good, solid six months of research and development here at Double Negative, where our programmers worked like the blazes and developed this fantastic new suite of tools, which allowed us to do the show. This pretty much allowed us to accommodate all of the different things that then happened as we went along through the film. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]So we moved from a position where, at the outset of the film, Chris was pretty adamant that he wasn’t going to have digital cityscapes, certainly not entirely digital cityscapes, in the film, to a position, at the end of post-production, where Chris is approaching his final cut of the film and is coming up with new ideas for shots, and we’re able to generate them entirely digitally, because obviously there is no opportunity to go out and shoot new material at this point. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]DF: So his original vision was to do things completely naturalistically? [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: Or to restrict visual effects to things like matte painting extensions of cityscapes and for backgrounds, and whenever we were looking at foreground architecture, to always have that as real stuff in-camera. But as the film progressed, I think Chris became more and more comfortable with what we were doing and what we were able to give him. And he would ask for something and we would give it to him, not come back and say, “Well, we can’t do this, and we can’t do that.” Because we’d had this long period to plan and decide how we were going to approach things. He became pretty confident we could achieve the things he was after. So we ended up with sequences in the final reel of the movie, in the train sequence, where we’re cutting back to back between completely CGI shots for about five shots in a row, at one point. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]

One thing the newer crop of superhero and sci-fi films are doing right is using effects to enhance the story, not overshadow it.

One thing the newer crop of superhero and sci-fi films are doing right is using effects to enhance the story, not overshadow it.

DF: There have been, over the past 10 years or more, a whole raft of visual effects-filled superhero and science-fiction films. In the evolution of the technology and the ability of things you can do, how have things progressed since the Spider-Man films, the X-Men films, The Matrix and Star Wars? [/FONT][FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: The most satisfying thing in the way that visual effects have developed over just the last few years, over the films that you mentioned, is that filmmakers, directors, screenplay writers, and art directors, have all really begun to embrace the possibilities digital filmmaking allows them. [/FONT]

DF: There have been, over the past 10 years or more, a whole raft of visual effects-filled superhero and science-fiction films. In the evolution of the technology and the ability of things you can do, how have things progressed since the Spider-Man films, the X-Men films, The Matrix and Star Wars? [/FONT][FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: The most satisfying thing in the way that visual effects have developed over just the last few years, over the films that you mentioned, is that filmmakers, directors, screenplay writers, and art directors, have all really begun to embrace the possibilities digital filmmaking allows them. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]In the case of Batman Begins, it’s a sort of hybrid approach of very traditional techniques and state-of-the-art digital effects techniques all combined together to make a film which is an enhanced version of what you would be able to achieve if you were just doing it traditionally. It was really interesting that in Batman Begins you saw Chris Nolan basically progress through all the various stages that visual effects have been through in the last five or six years. He went from being very reluctant to use extensive digital effects work, to the point where he was pretty happy for us to go away and generate something entirely digitally, because we were getting what he wanted. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]It’s almost like there’s been a real maturing of the visual language of visual effects, so that it’s now become incorporated into the broader language of cinematography in general. A lot of the stuff that we refer to as traditional, 60, 70 years ago were state-of-the-art. When somebody came up with the idea of doing matte paintings f or Douglas Fairbanks in Thief of Baghdad, that was pretty radical stuff. Before that it was a case of, well, surely you just go out and film stuff that’s real and cut it together and that’s how you made your film. The effects technicians of the day were taking it further. Then, because you give it this sort of credibility of history, suddenly it’s an established visual technique. Really, all we’re doing with digital special effects is taking that kind of thing one stage further. We’re offering greater flexibility. We’re offering a broader palette that the filmmakers can paint from. That, for me, has been the real key to the way things have developed. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]DF: What’s coming up that you’ll be able to do with visual effects — in two years, in five years — that you can’t do now? [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: In terms of where it’s going, I think you can imagine that process going even further. Instead of digital effects being something that’s done at the end of the day, after the film has been shot, we’re now beginning to see more and more films being made in the way that we did Batman Begins. The visual effects teams are brought on very early in the filmmaking process, so we can actually contribute to the whole creative process in which the decision-making’s getting made up front. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]Some of the stuff that I was really pleased with in the work that we did was the way that, for instance, whenever we flew the helicopter down the streets of Chicago, the city authorities cleared all the traffic from the street, so there’s nobody on the street, so it just looks like it’s deserted. But, obviously, we had to bring the life back, so we had to return all the traffic and all the pedestrians to the street, and they’re all created digitally and added in there. Those are just the sorts of incidental things that give filmmakers a greater scope to realize their work. I think you’ll start seeing stuff where the actual stock from the pre-visualization process of filmmaking, where at the moment we use very low-resolution animation, very sort of sketchy, basically like moving storyboard, in a couple years time, you’ll be able to do stuff that actually looks like the finished thing at that stage, to really give the filmmaker an idea of, well, what are you going to do? Where are you going to take it? [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]So they won’t have to guess, they won’t have to cross their fingers and say, “I hope these guys can make this look totally real.” You’re going to see increasingly realistic humans created digitally, and you’ll also see, I think, landscapes and environments. You look at something like the recent Star Wars movies, and there are some incredible landscapes and environments in there. But they work because they are fantasy environments. But re-creating scenes and environments of historical things which are long past, yet making them feel like you could actually be there and really see them, that’s the sort of thing I thing I think you’re going to see more and more of. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]I also think you’ll start seeing filmmakers using visual effects in a non-realistic way, by which I mean the kind of work that we saw in films like The Matrix and Twister, where you’ve got a subjective approach to the way that the film is made. Events will be portrayed from the observer’s point of view rather than some sort of slavish adherence to objective photorealism, whatever that means. In other words, a more expressive way of using visual effects, rather than it just being eye candy. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]Danny Fingeroth was the longtime editorial director of Marvel Comics’ Spider-Man line and consulted on the 1990s Fox Kids Spider-Man animated series. He has written hundreds of comics stories, and written and developed characters and scripts for animation, most recently episodes of 4Kids Ent.’s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]Fingeroth is also the author of Superman On the Couch: What Superheroes Really Tell Us About Ourselves and Our Society (Continuum), and puts out Write Now! Magazine, the premier publication about writing for comics and animation, through TwoMorrows Publishing. He teaches Writing for Comics and Graphic Novels and moderates seminars with Graphic Novel creators at New York University and the Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art. Fingeroth is a frequent guest on radio and television (including E! Ent. Television, the Today Show and NPR’s All Things Considered), commenting on comics and on popular culture in general. His op-eds and comments on superheroes and pop culture have appeared in many newspapers and websites, including the Los Angeles Times, the Baltimore Sun, USA Today and cnn.com. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif] [/FONT]

Comic pro Danny Fingeroth talks with Double Negative’s visual effects supervisor Paul Franklin about bringing Batman Begins to the big screen.

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]Paul Franklin: The key thing for this movie, throughout production and post-production, and in every aspect, is that [director] Chris Nolan really wanted this to be very much grounded in some sort of believable reality, rather than existing purely inside some sort of graphic world that could only be achieved through the use of computer animation or whatever. And he always wanted to make it feel like that you might actually go to Gotham, that Gotham might be a real place and that somebody could really do the things that Batman was doing. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]So, particularly with our work for creating the character of Batman, the majority of what you’re looking at on film is real stuntwork. It’s either Christian Bale dressed as Batman, or his stunt double, Buster, who did some incredible stuff. And there was some amazing work put together by the stunt crew for the show. But there were a few moments where we used digital effects to basically extend what the stunt crew had already achieved, and just basically carry the action off in ways that perhaps are a little bit too hard to rig at the moment. For instance, Batman is equipped with various types of high technology that he uses in his battle against crime. He has the ability to fly — or, to be more precise — to glide, with the aid of the Bat-cape. And the special effects guys put together a really impressive flying rig for Batman. But one thing that it wasn’t really capable of doing was deploying in flight. So, for instance, when Batman jumps off the top of a building and goes down the side of a building, and then his loose-flying cape suddenly deploys into the hang glider shape, bat-wing shape — that’s something we achieved digitally, through digital stunt double work. But, at every point, Chris Nolan was really, really keen that it shouldn’t look like this guy has suddenly sprouted wings and is able to fly like a bird-man. He basically is now turned into, say, a hang glider or a parasail, or something like that. And so that effect was based on: what might it be like if this guy was equipped with some kind of high-tech parafoil? How might he fly? [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]DF: Well, you certainly achieved that. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: Batman’s not capable of incredible muscular feats that would require him to be superhuman and have unbelievable, godlike strength. But he’s equipped with this incredible Kevlar body suit that has an endoskeleton, and all this sort of stuff. So that’s the type of thing we were doing. And in order to make that all work, we had to, first off, make very, very detailed models of Christian Bale dressed as Batman in the Batman costume. We had to study the Batman costume so we could reproduce it with fidelity in the digital world, so that you wouldn’t notice the difference between the digital Batman and the live-action Batman. Because we actually cut seamlessly within a couple of shots from a stunt double to the fully digital Batman. We wanted to make sure that was seamless, because we didn’t want it to certainly look like it was turned into an animated character at that point. And then, when we we’re doing the stuff that we’re doing as digital effects, we’re always basing it on some sort of actual reference. So, for example, for the shot in the movie, where you see Batman dive down the side of a building and then deploy his wings and “fly,” it’s an entirely digital shot. We actually had access to Buster, and he and the stunt crew staged the special reference stuff for us. Buster went up on top of one of the large buildings inside the giant set in Cardington, which is about eight stories high, and did a wire jump off the side of the building — which he repeated 10 times. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]We mounted 10 video cameras manned by members of the Double Negative visual effects team, and recorded Buster from every possible angle doing this repeated action. He did it with and without the bat wings, so we could get a feel for how he might fall, and how the wings might behave in the slipstream. So all our stuff was always based on some sort of actual reference that we always have.[/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif] DF: Is there anything you want to add about the effects being seamless and fitting in with the overall naturalistic look of the film? [/FONT][FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: Chris is a very interesting filmmaker in that he’s a young guy and he has a very hands-on approach to filmmaking. Now, Batman Begins is a very big-budget film, probably one of the biggest-budget films made this year. Quite often, in that kind of filmmaking, the director will spend a lot of time working with the principal cast and crew, but he’ll let stunt sequences and visual effects sequences be handled by a second unit. Well, with this film, there was no second unit. Chris and Wally Pfister, the director of photography, shot everything. Every frame you’re looking at there has pretty much been authored by Chris and Wally. They’re involved. Chris is involved in everything that went into the film. And what’s also very interesting about this film is that they’re very into the whole technology of filmmaking in the traditional sense, in that this film does not have a digital intermediate. It wasn’t taken to a digital lab. It’s all graded in the traditional way, in a film laboratory. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]It was this level of scrutiny that was applied to every aspect, whether it was creating the digital reproduction of the way that a camera actually captures the light, to the way that we had to prove that we could do convincing, photorealistic digital architecture to be able to create the digital cityscapes of Gotham City. We actually went out and we chose a suitably art deco building here in London and photographed it on a variety of different films and still formats, on an extremely cold day here in January about a year ago. We filmed the sun rising, so we were there before the dawn. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]That was also an interesting foresight of what was to come, because we were perched on the tops of buildings, looking at this other building, in fairly precarious positions. And eventually we ended up in Chicago, standing on top of the very top ledge of the Sears Tower photographing the dawn rising over Lake Michigan. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]DF: Tell us more about the lighting and modeling used to achieve the effects that you wanted. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: Well, Chris isn’t somebody who will come up with a whole bunch of storyboards and approve a whole bunch of previsualization animation, and say, “OK, this is what we’re going to do for the film.” He was very keen that this film should not be overwhelmed by CGI and end up becoming a cartoon. This extended all the way back to the pre-production process, where he didn’t want to produce animatics. He didn’t want to have, say, a story reel of the film, which he would then just go out and shoot. He likes to make a lot of his creative decisions when he’s actually on the set, because it might be that the actors respond differently to actually being in Chicago or something like that, and get some interesting things that you couldn’t predict were going to happen. If you’ve got this sort of predefined, rigid structure, which you’re going to shoot, then you can’t respond to that, you can’t make use of it. So he would often see things and say, “OK, this is a cool thing, this is what I want to get in the film.” However, we had to be able to plan for what we were going to do to be able to create the digital environments later on. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]And so we went out in May for a two-week visual effects shoot, which is in advance of the main unit turning up in August in Chicago. We knew there were a variety of locations that were going to be in the film, and a variety of different types of environments that we needed to get, but we didn’t know exactly what they would be, and where the camera was going to be pointing and how the scene was going to be lit. So we developed a process that allowed us to photograph very high-resolution panoramas of the Chicago cityscape across a very wide range of exposure. This means that we could take environments that we’d shot under ambient Chicago city light conditions — in other words, just the lighting you would see if you went to Chicago this evening and pointed a camera at the buildings — and then, because we had this very, very high dynamic exposure range, we could then relight these images through the use of computer graphics so we could match the theatrical lighting, which Wally then put on the locations when the main unit showed up later in the year. They used some pretty impressive lighting rigs on the days when they were shooting stuff, particularly for the car chase sequence, when the Batmobile is on the rooftop of the parking garage just before it leaps off and goes into the crazy chase across the rooftops, which is all our work. We had to match all the environments around the miniature car chase sequence to match everything that came before that. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif] The other thing is that we had to build, for modeling, a very comprehensive library of Chicago structures, and also other structures that were hero buildings, like Wayne Tower, for example, which was an imaginary building which doesn’t really exist, obviously. Whenever you see Wayne Tower in the film, it’s an entirely digital creation. So that was something very key, to get it looking totally convincing and integrate it into the Chicago cityscape, to then create the landscape of Gotham.[/FONT] [FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]Now, basically, our 3D lighting toolset was designed to mimic the way you would work on a real set, instead of working in arbitrary values of intensity of light and things like that. You can do things in a 3D universe, which are completely non-naturalistic. They don’t obey any laws of physics. And this was the sort of thing that Chris objected to. He would say, “Well, as soon as you start breaking the rules, then the scene inherently loses its believable look. It starts looking like a cartoon. It starts looking like a contrivance.” So we were very keen to make sure that our office would always talk in terms of photographic stops. And so they would say, “OK, so you want to raise the exposure on this scene?” Rather than just, “Make it brighter, increase the intensity by this amount,” you actually talk in terms of photographic stops. And so if Chris would say to us, “OK, that needs to be two stops brighter,” I could say to my 3D artists, “Make it two stops brighter,” and it all meant the same thing to everybody. We all used the same language. That was quite conscious. So it was more about making the digital environment user-friendly. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]DF: It’s the way a computer interface becomes simplified. You don’t need to know all sorts of code to use it. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: Exactly. One of the key things is also that it means that our artists are also thinking in a more creative, more artistic fashion. They’re not looking at everything through the interface of all the technical layers that get laid on top, and they start thinking more about, “What is it I’m actually doing here? What am I actually doing with these images? How am I making these images so that they evoke an emotional response, that they fit with the feeling of the live-action photography, and that they tell a story?”[/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif] DF: What was gained by using a virtual city, albeit one based on real places, instead of simply going on location in an actual city? [/FONT][FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: One of the key places where Batman Begins really goes into the realms of the fantastic is that the sheer scale of Gotham City is way beyond anything that you could ever see in a real city. Now, Chicago is incredibly impressive. If you go up to the top of the Sears Tower and look out, you think, “This is quite an incredible landscape.” Especially compared to anything we have over here in Europe. I mean, London’s an enormous city, but it just doesn’t have that sheer gargantuan size at the center of it that big American East Coast cities have. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]At the same time, Chris really wanted it to feel like Gotham’s a city out of control, sprawling in all directions, a true mega-city. There’s a moment quite early on in the film, where Bruce is returning from his sojourn in the Himalayas, and he’s flying back into Gotham with Alfred on board the Wayne Enterprises private jet. Bruce looks out of the window and he sees the sun rising over Gotham City as they fly in from the sea, and the sun is glittering off the sea — that’s an entirely computer-generated shot. There’s no live action in that shot. Everything that you’re looking at there is computer-generated. But it’s always based on a reality. All of the buildings in the city are based on Chicago originals, and the look and feel of it is inspired by the way that New York is broken up into islands. The lighting design is based on the photography that I did from the top of the Sears Tower, watching the sunrise over Lake Michigan. But the scale of it is enormous. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]DF: So Wayne Tower is the only made-up building in the thing? [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: Yes, although, obviously we have things like the monorail system, which is a non-real thing. That was inspired by the Chicago El train, but it’s been taken into the realm of the fantastic by suspending it 150 feet up in the air with these incredible sort of mid-twentieth century ironwork structures. It has this almost sort of Victorian, industrial revolution feel to it. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]DF: Was that based on actual designs, actual buildings from the Victorian era? [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: What they were all based on was the actual structure of the Cardington, the building that was used here in the U.K. as a studio, which is a vast hangar, which was built just after the First World War to house an airship called the R-101, which was the size of the Hindenburg — 800 feet long. The building is quite incredible. It’s a single structure, one giant room, which is about 200 hundred feet high and about 200 feet wide, and a quarter of a mile long. But it’s supported by this unbelievable grid structure inside of it, the girder structure that supports the roof, and that was the inspiration, I believe, for the monorail towers.[/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]DF: But, say, the scene on the glacier — were there any visual effects done on that? [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: The big moment in the scenes in Iceland is when we establish the monastery for the first time, where you see the monastery on the side of a mountain through a snowstorm. And the monastery is a miniature, of course, because there isn’t a real monastery that looks like that, and there certainly isn’t one in Iceland. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]But everything that you’re looking at in terms of the environment in those scenes, with the snow falling, all that sort of stuff, that’s all been created digitally, as well. I’d say that’s an example of scene effects where people wouldn’t notice that something was going on. Perhaps the best moment for that is, at the end of that whole sequence where Bruce Wayne is walking towards the private jet parked out on the runway. That was actually shot at a rather rainy airfield north of London, so surrounding the plane was just flat, green, rolling fields, and some housing in the far distance. We replaced the background with a digital matte painting, which I think is pretty seamlessly integrated there. It makes it look like you’re still in the Iceland environment. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]DF: Were there any visual effects you tried for in the movie that didn’t work and couldn’t be used? [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: I’d say no. There wasn’t really anything that we tried that didn’t work out, because we were in a very lucky position on with this film. We got involved on the movie right at the beginning, during preproduction. We were involved in all of the pre-planning phase, so we were able to actually sit down with the guys and work out the best way of going about shooting things, and what kind of material we needed to get, and what kind of tools that we needed to develop. We then were able to have a good, solid six months of research and development here at Double Negative, where our programmers worked like the blazes and developed this fantastic new suite of tools, which allowed us to do the show. This pretty much allowed us to accommodate all of the different things that then happened as we went along through the film. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]So we moved from a position where, at the outset of the film, Chris was pretty adamant that he wasn’t going to have digital cityscapes, certainly not entirely digital cityscapes, in the film, to a position, at the end of post-production, where Chris is approaching his final cut of the film and is coming up with new ideas for shots, and we’re able to generate them entirely digitally, because obviously there is no opportunity to go out and shoot new material at this point. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]DF: So his original vision was to do things completely naturalistically? [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: Or to restrict visual effects to things like matte painting extensions of cityscapes and for backgrounds, and whenever we were looking at foreground architecture, to always have that as real stuff in-camera. But as the film progressed, I think Chris became more and more comfortable with what we were doing and what we were able to give him. And he would ask for something and we would give it to him, not come back and say, “Well, we can’t do this, and we can’t do that.” Because we’d had this long period to plan and decide how we were going to approach things. He became pretty confident we could achieve the things he was after. So we ended up with sequences in the final reel of the movie, in the train sequence, where we’re cutting back to back between completely CGI shots for about five shots in a row, at one point. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]In the case of Batman Begins, it’s a sort of hybrid approach of very traditional techniques and state-of-the-art digital effects techniques all combined together to make a film which is an enhanced version of what you would be able to achieve if you were just doing it traditionally. It was really interesting that in Batman Begins you saw Chris Nolan basically progress through all the various stages that visual effects have been through in the last five or six years. He went from being very reluctant to use extensive digital effects work, to the point where he was pretty happy for us to go away and generate something entirely digitally, because we were getting what he wanted. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]It’s almost like there’s been a real maturing of the visual language of visual effects, so that it’s now become incorporated into the broader language of cinematography in general. A lot of the stuff that we refer to as traditional, 60, 70 years ago were state-of-the-art. When somebody came up with the idea of doing matte paintings f or Douglas Fairbanks in Thief of Baghdad, that was pretty radical stuff. Before that it was a case of, well, surely you just go out and film stuff that’s real and cut it together and that’s how you made your film. The effects technicians of the day were taking it further. Then, because you give it this sort of credibility of history, suddenly it’s an established visual technique. Really, all we’re doing with digital special effects is taking that kind of thing one stage further. We’re offering greater flexibility. We’re offering a broader palette that the filmmakers can paint from. That, for me, has been the real key to the way things have developed. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]DF: What’s coming up that you’ll be able to do with visual effects — in two years, in five years — that you can’t do now? [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]PF: In terms of where it’s going, I think you can imagine that process going even further. Instead of digital effects being something that’s done at the end of the day, after the film has been shot, we’re now beginning to see more and more films being made in the way that we did Batman Begins. The visual effects teams are brought on very early in the filmmaking process, so we can actually contribute to the whole creative process in which the decision-making’s getting made up front. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]Some of the stuff that I was really pleased with in the work that we did was the way that, for instance, whenever we flew the helicopter down the streets of Chicago, the city authorities cleared all the traffic from the street, so there’s nobody on the street, so it just looks like it’s deserted. But, obviously, we had to bring the life back, so we had to return all the traffic and all the pedestrians to the street, and they’re all created digitally and added in there. Those are just the sorts of incidental things that give filmmakers a greater scope to realize their work. I think you’ll start seeing stuff where the actual stock from the pre-visualization process of filmmaking, where at the moment we use very low-resolution animation, very sort of sketchy, basically like moving storyboard, in a couple years time, you’ll be able to do stuff that actually looks like the finished thing at that stage, to really give the filmmaker an idea of, well, what are you going to do? Where are you going to take it? [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]So they won’t have to guess, they won’t have to cross their fingers and say, “I hope these guys can make this look totally real.” You’re going to see increasingly realistic humans created digitally, and you’ll also see, I think, landscapes and environments. You look at something like the recent Star Wars movies, and there are some incredible landscapes and environments in there. But they work because they are fantasy environments. But re-creating scenes and environments of historical things which are long past, yet making them feel like you could actually be there and really see them, that’s the sort of thing I thing I think you’re going to see more and more of. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]I also think you’ll start seeing filmmakers using visual effects in a non-realistic way, by which I mean the kind of work that we saw in films like The Matrix and Twister, where you’ve got a subjective approach to the way that the film is made. Events will be portrayed from the observer’s point of view rather than some sort of slavish adherence to objective photorealism, whatever that means. In other words, a more expressive way of using visual effects, rather than it just being eye candy. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]Danny Fingeroth was the longtime editorial director of Marvel Comics’ Spider-Man line and consulted on the 1990s Fox Kids Spider-Man animated series. He has written hundreds of comics stories, and written and developed characters and scripts for animation, most recently episodes of 4Kids Ent.’s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif]Fingeroth is also the author of Superman On the Couch: What Superheroes Really Tell Us About Ourselves and Our Society (Continuum), and puts out Write Now! Magazine, the premier publication about writing for comics and animation, through TwoMorrows Publishing. He teaches Writing for Comics and Graphic Novels and moderates seminars with Graphic Novel creators at New York University and the Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art. Fingeroth is a frequent guest on radio and television (including E! Ent. Television, the Today Show and NPR’s All Things Considered), commenting on comics and on popular culture in general. His op-eds and comments on superheroes and pop culture have appeared in many newspapers and websites, including the Los Angeles Times, the Baltimore Sun, USA Today and cnn.com. [/FONT]

[FONT=Verdana, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif] [/FONT]

© 1996 - 2009 AWN, Inc. All rights reserved.

No part of this article may be reproduced without the written consent of AWN, Inc.

No part of this article may be reproduced without the written consent of AWN, Inc.